Editing

Complicating Prose and Verse Lineation through Digital Editions of Early Modern Drama

Primary Contributors: Bernadette Myers, Columbia University and Robert Yates, Georgetown University

Module Overview

Many early modern literature courses alert students to distinctions between prose and verse, particularly when both forms occur in the same text. With this in mind, we propose a sequence of lessons, which might be integrated into a broader early modern literature course that uses digital tools to

- review the distinctions between prose and verse

- complicate the terms “prose” and “verse”

- teach how one develops an argumentative, interpretive thesis rooted in analysis of text structure

- situate texts in the context of material production

Lesson Objectives

Students will review the distinctions between prose and verse in early modern plays through a close analysis of Christopher Marlowe’s The Massacre at Paris.

Students will examine the Early Modern English Drama’s preservation of the original playbook’s messy lineation in order to theorize the shifting use and function of prose and verse lines.

Student will analyze the role of early modern printers and contemporary editors in (re)lineating and thus remediating the text.

Time: Three 45-minute class periods.

Materials:

- The Folger Digital Anthology of Early Modern English Drama (EMED)

- The Massacre at Paris, Christopher Marlowe

- The Puritan, W.S. (later attributed to Thomas Middleton)

- Christopher Marlowe: The Complete Plays (Penguin Classics edition)

- The puritan; or, the widow of Watling-Street (EEBO edition)

Assessment Description:

- Short essay: Reflect on the textual authority of Massacre in the original print edition, reflected in the EMED edition as well. Why might we, or other editors, want to re-lineate a line when the original printing of the play maintains an unclear prose/verse lineation? Does the printer Edward Allde provide us with the “authoritative” version of how the text should be read? Does EMED? How does editing or printing a text also require some form of interpretation? Your response should be one to two pages.

- Short project: Select thirty lines from Massacre and create a critical edition of the excerpt. Your notes should include how your edition maintains and diverges from the documentary edition and how your editorial decisions affect readings of the scene.

Lesson Sequence

Day One: Prose and Verse

- Remind students what they may already know about the differences between a prose and a verse line. It may be helpful to provide a familiar example.

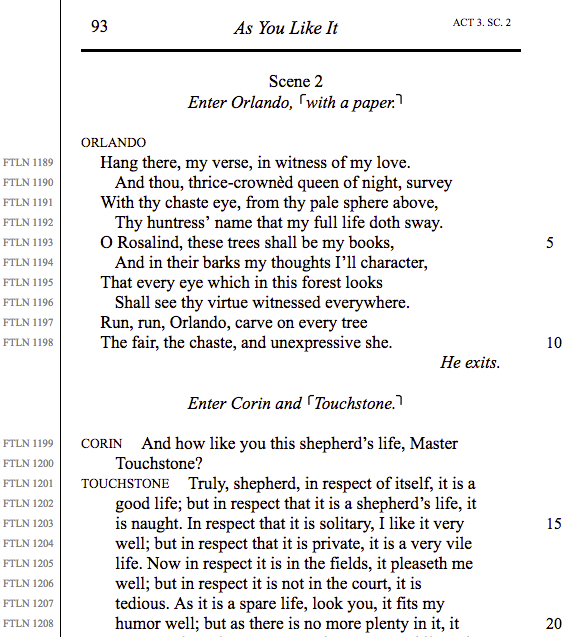

- Review an example from Shakespeare. For example, the first twenty lines of Act 3, Scene 2 from As You Like It (though any scene with mixed verse and prose will do).

- Explain to students how Orlando’s speech is a perfect model for blank verse (it is, in fact, an embedded sonnet). Review the iambic pentameter by having students read aloud together and clapping on the stressed syllables.

- Read aloud Touchstone’s speech as a model for prose.

- Class discussion: What are some possible theories about why characters speak in prose or verse? What is a testable hypothesis for what prose and verse might indicate?

- Some possible answers could include: class differences, different language uses (wooing scene vs. conversation), different affect (rational vs. passionate), idealism versus cynical commentary, scenes of everyday live versus a staple image of court culture.

- Display this list on the board as the activity progresses.

- In small groups or in a homework assignment, students practice the skill of distinguishing prose from verse and theorizing their effects.

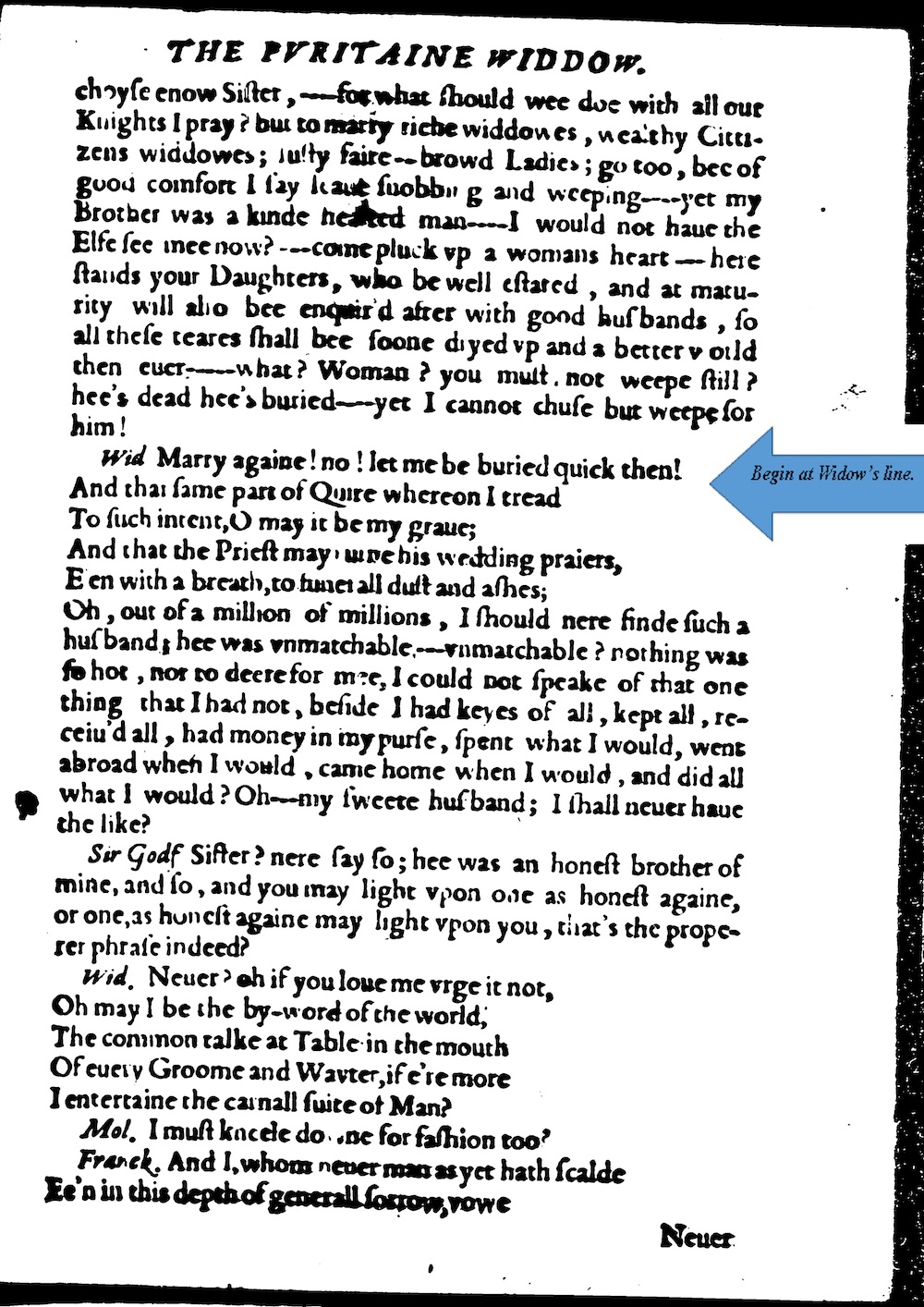

- Use an excerpt from The Puritan and ask students to read and discuss how the lineation in the 1607 edition might affect how readers think about the scene. Furthermore, what might the lineation of verse and prose in this scene indicate?

- Background information: The Puritan (1607) is a city comedy about a recent widow and her two daughters, who are nearly swindled by sinister scholar. The following excerpt is from Act 1, Scene 1 and shows the Widow Lady Plus speaking with her brother-in-law, Sir Godfrey.

- Introduce students to Christopher Marlowe’s The Massacre at Paris and then assign homework.

- Homework assignment: Read the EMED edition of Massacre. For one scene, students highlight lines written in prose and underline lines written in verse. Students might place a squiggly line under lines with unclear prose/verse status.

Day Two: Re-lineation

- Split students into small groups. Ask them to compare their prose/verse mark-up and to discuss points where their mark-up diverges or moments that were difficult to determine.

- Select three contentious passages to discuss as a class. Why might we mark these lines as prose? Why might we mark them as verse? A good problem moment to focus on might be Guise’s speech (B1r-v).

- Introduce the concept of editorial re-lineation. How would the students prefer to re-lineate the lines in order to distinguish between prose and verse? How might they re-lineate the lines to help a reader better understand the meaning of the passage?

- Provide an example of the re-lineated passages from an edited version of the play (the Penguin Classics edition is a good example).

- Extrapolate further from the close reading level to the play at large: How do their small re-lineation decisions alter the meaning of a particular passage? Would they affect their reading of the play as a whole?

- Who are the actors contributing to the mediation of the play’s verse or prose lines?

- Assignment: Students choose one “problem” passage to re-lineate so that prose and verse lines are easily identifiable. Students write a one paragraph reflection on how their re-lineation clarifies the meaning of the passage.

Day Three: Early modern printing

- Introduce students to Early English Books Online (EEBO).

- Have them find Massacre in the EEBO database and look for the images associated with the problem prose/verse passages identified by the class. What are the differences between their own re-lineations and those of the original text? What about those of the Penguin edition?

- Assign assessment.